Game Research That Fits Every Stage of Development

- October 23, 2025

- Michał Dębek

- Every Game Starts with a Hypothesis

- Project Wraith: The Napkin Sketch

- Game Concept — Does the Experience Make Sense?

- Pre-production — Does the Core Loop Work?

- Production — Does the Game Work as a Whole?

- Right Before Launch — Does the Promise Match the Experience?

- After Launch — The Roadmap Compass

- Success of the Game Isn’t Luck. It’s Research Done Right.

These are lessons from the Project Wraith Production Cycle. A practical guide to UX and Game User Research — from early concept to post-launch. See which methods help validate design hypotheses and fine-tune the player experience.

If you’d rather listen than read, you can hear this article as a podcast episode:

Game development is a mix of creative thinking, hypothesis testing, risky decisions, technical implementation, and endless iteration. In a mature production pipeline, this entire cycle is driven by hypotheses about the intended player experience. A game is never an objectively functioning product; it’s a system — an environment built to make certain things happen in the player’s mind.

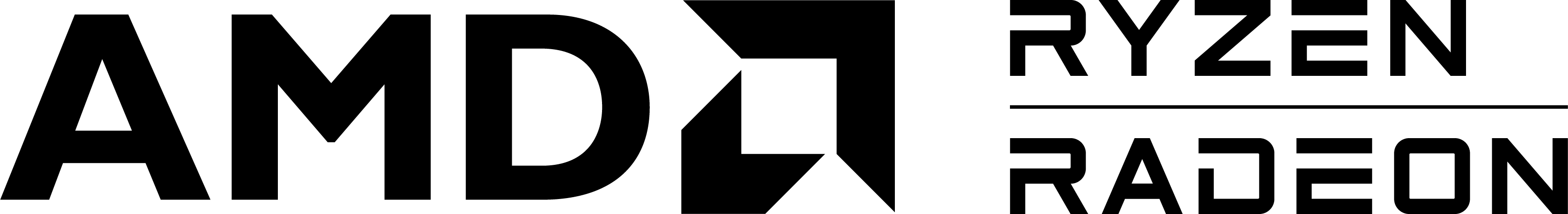

Every Game Starts with a Hypothesis

Game creators begin by forming hypotheses about how their game will interact with the player’s mind — how it will tap into emotions, desires, or even basic psychological needs. They address these hypotheses through the mechanics, narrative, and aesthetics they believe will best evoke the intended experience.

Let’s imagine a fictional case.

As teenagers, we devoured Lem and Simmons. Later, we worked in a studio making survival games. Eventually, we founded our own team — eager to create a game that we would genuinely enjoy building. From psychology, we know there’s a large group of people constantly seeking adrenaline. From SteamDB data, we can also see how strongly players respond to sci-fi aesthetics. We want to make science fiction, and we already know how to build around survival mechanics.

So we form a convenient hypothesis:

there’s a segment of players driven by the need for adrenaline, for whom the optimal experience is immersion in a world built on the logic of a survival horror — scarce resources, constant threat, and a dopamine rollercoaster. To that, we add a hard sci-fi aesthetic, since cosmic darkness pairs naturally with tension and fear of the unknown.

We sketch out a concept: a sci-fi survival horror set in a futuristic world, built around futuristic gear and the story of an isolated space outpost that suddenly went dark. Let’s call it Project Wraith.

Takeaway:

- Game planning starts with a player-experience hypothesis. You’re designing emotions, not a feature list.

- You need a mental picture of your audience backed by real market data.

- The initial concept is only a starting point for research and validation.

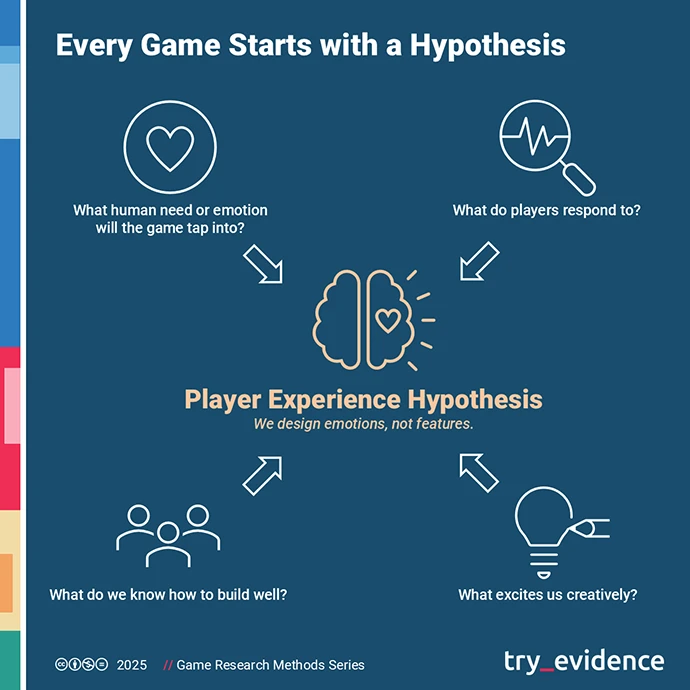

Project Wraith: The Napkin Sketch

Everything seems to line up: we have experience with survival titles, a fascination with science fiction, and the confidence that we can fuse both into something unique. Production risk looks low. Enthusiasm is high.

After a few conversations with potential publishers, that confidence only grows stronger. We can see there’s a market buzz around sci-fi survival horror, and publishers are open to the idea.

Publishers, of course, are constantly forming their own hypotheses about what will sell well in the mid- and long term. They base them on historical data, industry chatter, prior experience with different line-ups, and, sometimes, large-scale market research.

So we start building the game. We’re lucky enough to find a publisher who signs with us, assuming — on their end — that the business risk is low. They, in turn, form their own hypothesis: that this type of game will be easy to promote to a big enough audience for the investment to pay back many times over. In short, a hypothesis of profit.

That’s how almost every production starts — from an idea that is, at its core, a hypothesis about human experience.

The publishing process starts the same way: with a hypothesis that players want to hear a certain promise, and that they’ll gladly pay to experience it.

Research — both qualitative and quantitative — is how these hypotheses are continuously tested. Without it, you risk waking up to an expensive product that fails to deliver the experience its creators imagined. Or, as a publisher, promising an experience that nobody actually wants, except the developers. Or a 60-dollar game that feels worth five; a promise that players perceive as broken; or a feature that’s missing where players care most.

Takeaway:

- A napkin sketch isn’t proof of concept. It’s an early alignment between the team’s ambition, market intuition, and the publisher’s sales hypothesis.

- There are two risk loops to manage: the developer’s loop, testing the emotions and mechanics; and the publisher’s loop, testing the market promise.

- Qualitative and quantitative research prevent costly mistakes at the source — chasing non-existent player needs or imaginary market segments.

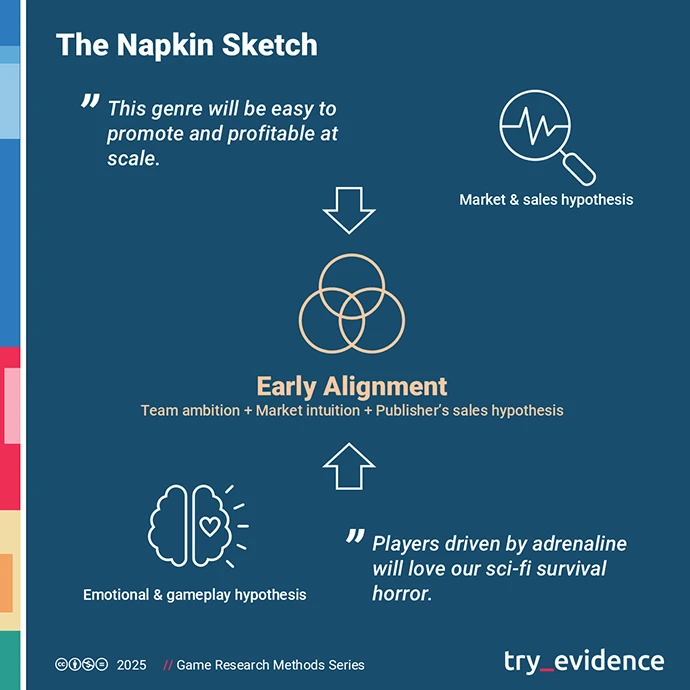

Game Concept — Does the Experience Make Sense?

The first round of research a game should go through must answer one core question:

Do the emotions and assumptions we’re designing for actually have an audience?

And if they do, is that audience large enough for the game’s price point to cover production and marketing costs — and still deliver a profit margin?

We start with a Design Assessment — a review of the concept: documentation, pitch decks, visual references, and sometimes even early world sketches. We look for originality, internal consistency, and logic. We analyze which other titles occupy a similar space in players’ minds and how this one could stand out.

At this stage, we don’t ask players what they think about a game that doesn’t yet exist. Instead, we observe how they behave naturally: we analyze communities on Discord, Reddit, and Steam, read threads about similar titles, and study comments under trailers and gameplay videos.

In research language, that’s digital ethnography (observing player behavior and language in their natural habitat), cultural desk research (analyzing existing discussions and media around the genre), and insight research (extracting recurring motivational patterns and expectations from those observations).

These anthropological methods help us understand how players talk about a genre niche and what they truly expect from it. At this point, we’re not interested in what players think about our idea, but in what genuinely moves them in games they already know and love.

We then complement that picture with quantitative data. From internal databases and external sources, we estimate how big the relevant segment is, which mechanics and settings are currently in demand, and which have burned out. This is where numbers come in — market size, trend-fit indicators, conversion potential.

From a psychological standpoint, we try to determine which human needs the game aims to satisfy. We use various frameworks — most notably the Psychogenic Equilibrium Theory of Gamer Motivation, which focuses on balancing psychological tension and satisfaction. In the spirit of Schell’s methodology, we translate that into an Essential Experience — a clear statement of what the player should feel, and why they’ll want to feel it.

In the case of our hard sci-fi survival horror, we quickly discovered the concept had potential but needed refinement. Core fans of the genre enjoy high difficulty and unforgiving mechanics. They’re drawn to villain protagonists, nonlinear stealth loops, bits of parkour, and other features we hadn’t even considered. See our article on survival horror fans for a deeper look at this audience.

These findings — a blend of desk research, psychological analysis, and quantitative sizing of player segments — help crystallize the game’s direction. We can now define clearer psychological promises and start shaping a meaningful, distinct USP — a unique, relevant, and easy-to-grasp promise that sets our game apart from the rest of the niche.

Takeaway:

- We validate demand and audience. We start with a Design Assessment and niche ethnography — we test players’ real expectations toward similar games, genres, and settings.

- We add numbers to what we observe: segment size, trend fit, conversion potential. We combine qualitative and quantitative methods.

- We define or redefine the Essential Experience and USP, and prepare a list of hypotheses for the next testing stage.

Pre-production — Does the Core Loop Work?

A playable prototype finally comes to life. After months of concept work and documentation, we can actually play Project Wraith and see whether it delivers the intended experience.

Before jumping into prototype testing, though, we can already collect quantitative declarative data. With a polished concept — world description, defined core loop, key features, and basic visuals — we can run concept tests or price-sensitivity studies. These reveal not only how players perceive the idea, but also its perceived value and acceptable price range.

Anyway, this is the first moment when we test how the idea works in action: the rhythm of gameplay, the type and intensity of emotions, and the player’s reactions to core mechanics. In practice, we launch the full set of Game User Research (GUR) methods — observing player behavior, emotion, and experience during real gameplay.

We usually start with lab-based playtests. Carefully selected participants from the target segment come to the lab — players matched to the game’s intended motivations, engagement levels, and genre preferences. Tight control over who plays lets us draw reliable insights from exceedingly small samples.

We watch how players behave: where they stop too long or rush ahead, where they lose purpose, where tension turns to frustration, or where they get completely stuck. Afterward, in-depth interviews help us understand the whole experience — what they liked, what they felt, what they remember, and when they lost or regained a sense of control.

Sometimes we add Engagement Tracking — measuring gaze activity (eye-tracking), heart rate, micro-expressions, and skin conductance (EDA) to pinpoint real moments of emotional tension. That lets us see how emotion flows through the player over time. Read more about these biofeedback methods in our dedicated article.

In UX research terms, this means usability testing and experience-flow measurement. We rely on established tools and scales, sometimes expanded by us with elements specific to each lab task.

Playtests for Project Wraith deliver surprises. Players do feel tension — but it comes not from level design, rather from navigation chaos, unconventional key mapping, and the only available melee weapon: a kind of lightsaber that feels like a medieval two-handed sword. In several sessions, players put down the controller with sarcastic comments about the combat that “feels more like drawing intricate patterns with a brick instead of fighting like a Jedi commando.” Instead of the desired adrenaline rush, frustration takes over.

Our research team analyzes player behavior, flow-break points, confusing feedback cues, and player narratives — what they felt, what they thought (which no sensor can capture), and what beliefs they ended the session with.

Findings turn into a short list of UX recommendations. A few targeted fixes can save months of development and hundreds of thousands of dollars in later sprints. Cognitively, this is not about whether the game makes sense — we already know that from earlier research — but whether that sense is perceived through gameplay.

In research language, we’re now closing the perception gap — the difference between how designers believe players experience the game and how players actually experience it. Empirical data helps reduce and measure that gap, and each iteration moves the project closer to alignment between intended and experienced gameplay.

Takeaway:

- We test the game in a controlled lab with small, precise cohorts. Observation and post-session interviews reveal the rhythm, friction points, and lived experience of the core loop.

- We combine behavioral data with metrics and biofeedback to pinpoint where and why frustration replaces the intended tension and flow.

- We iterate toward convergence. Each build–test–learn loop ends with a UX fix list and a new design question. Our goal is to close the perception gap.

Production — Does the Game Work as a Whole?

Project Wraith moves into full production. The game now has complete content, storyline, and mechanics that start to mesh together. This is when we check whether everything works as a coherent system — whether we haven’t broken the core experience by scaling the project and layering new elements: weapons, equipment, progression trees, quests, narrative, economy, and balance.

At this stage we combine qualitative and quantitative data. Simple playtests give way to comprehensive research cycles. We run two- or three-day studies where 8–12 players play through the entire game or large sections of it. We observe not only what they do but also how their emotional engagement and experience evolve over time. After each session, we conduct both individual interviews and focus groups (FGI) to understand which emotions persist and which fade amid the growing content.

As Celia Hodent wrote in The Gamer’s Brain, perception of a game always happens in a social context: players compare their feelings with others, interpreting meaning and emotion through shared cultural frames — memes, genre conventions, style, and narrative. That’s why we include focus groups: to observe the social dimension of play — how players’ emotions resonate, overlap, and collectively define difficulty, mood, or story coherence. The group dynamic triggers a “negotiation of meaning,” where participants challenge each other, refine their opinions, and spontaneously generate metaphors invaluable for designers and marketers alike.

In some builds, we introduce A/B tests — comparing, for example, different inventory systems or onboarding flows. We also bring in quantitative metrics, such as Net Promoter Score (NPS) or simulated review ratings. Telemetry data (e.g., death rates) is cross-referenced with interview findings to pinpoint where experience and frustration diverge.

We also run Expertly Analyzed Mock Reviews — simulated media reviews of the beta version. Journalists play the game and assess it as if reviewing the final product. This gives us a preview of how the title might perform in a crowded news environment, what narrative hooks attract attention, and what communication risks it faces. As trendsetters, journalists are also a great barometer of promise alignment — they see whether the game delivers on the hype we’ve been building, long before launch.

For Project Wraith, the test results were clear. Players described a strong sense of isolation but also a “flattening of tension” after the third hour of gameplay. Melee combat still felt unsatisfying. The team needed to rebuild weapon feedback, shorten mission length, add random dynamic events, simplify the map, redesign UI, and reduce tutorial prompts.

Journalists pointed out repetitive motifs, an overly dense interface, and tight release windows — issues that could hurt visibility for a title positioned as a hard sci-fi survival horror. They suggested shifting communication emphasis from survival mechanics toward the storyline, which they found intriguing.

Takeaway:

- We validate the game as a whole in long-form tests: 2–3-day sessions (8–12 players) and focus groups show whether the core experience holds up amid content growth and how the experience functions socially.

- We merge qualitative and quantitative approaches: observation, IDIs, FGIs, A/B testing (e.g., onboarding, inventory), and metrics such as NPS. We analyze where and why the flow drops.

- We assess market reception before launch. Expertly Analyzed Mock Reviews measure how the game might perform in the media and whether its promise aligns with the intended marketing narrative.

Right Before Launch — Does the Promise Match the Experience?

Launch or early access is the final collision of developer vision and marketing effort with reality. After years of development, Project Wraith is about to land in the hands of players, media, and influencers.

At this stage, we no longer test the quality of the game itself — in late beta or release candidate, there’s little room for fundamental changes. Instead, we verify whether the game experience matches what we’ve promised in communication.

A few weeks before launch, we conduct a store & comms validation — analyzing the Steam page, trailers, key art, copy, and the first minutes of gameplay. The research team and publisher jointly compare the marketing language with the actual experience of the first two hours of play. We need to be certain that what we’ve told the world really happens in the game.

We look for cognitive dissonances — moments where the player gets something different from what was promised, or where the promise appears without delivery. Players spot such mismatches instantly and react harshly, often demanding refunds.

Player satisfaction is, in essence, the difference between expectation and experience. That difference can be positive or negative; our job is to catch it when it’s negative, measure it, and understand its source — before frustration spills, e.g., into Steam reviews or media coverage.

We usually do this internally, with our research team supported by experienced industry journalists from major outlets — people capable of reading games and marketing language as critically as the target audience. Their perspective helps us see whether the game’s tone and promises align with what the first wave of players and media will actually perceive.

In Project Wraith’s final stretch, we discovered a few inconsistencies between the marketing narrative and the in-game experience. The publisher had been heavily emphasizing melee combat and weapon variety — which were solid — but journalists concluded that the game truly shined in its exploration arcs, lore, and story, not in confrontation.

In practice, what the publisher considered the main feature turned out to be just the backdrop for the real experience players valued most. So they adjusted the last promotional materials — trailers, screenshots, and store copy. The narrative didn’t change, but the promise was aligned with the game’s true experiential focus. The correction was small but crucial: early reviews after launch began to describe the game as “claustrophobic” and “about discovery,” instead of “lacking in pace.”

A subtle shift — but one that defined how Project Wraith positioned itself in players’ minds.

Takeaway:

- We verify the alignment between marketing promise and gameplay experience. We analyze marketing assets and the first hours of gameplay to ensure that communication truly reflects what players experience in the game.

- We identify cognitive dissonances — gaps between trailer, store copy, and actual play, as well as emotional shifts or unfulfilled promises — before they surface in public reviews.

- If needed, we adjust the tone of communication. Findings from validation studies — especially Silent Reviews — help us fine-tune messaging and highlight what players genuinely feel, without changing the game itself.

After Launch — The Roadmap Compass

Once the game is out, we no longer evaluate it in “good vs. bad” terms. Instead, we look for gaps in player experience — places where a small patch or a well-designed DLC could make a meaningful difference.

We start by carefully reading what already exists around the game: Steam reviews, Discord and Reddit threads, influencer content, and coverage in gaming media.

This is post-launch ethnography — identifying recurring themes and emotions that together form a coherent picture of what needs improvement or expansion.

In parallel, we talk to three cohorts of players: those who dropped the game early, those who played more than two hours, and heavy users — players who finished the game or even started New Game+.

In-depth interviews (IDIs) help structure the “whys” behind the patterns we notice in the community and media.

Meanwhile, quantitative data runs in the background — telemetry, Steam algorithm behavior, actual sales, ratios of comments to copies sold, refund statistics, and more.

For Project Wraith, the first post-launch weeks drew a clear map.

Part of the community asked for an exploration mode without time pressure; most players wanted stronger threat cues and tools that “fit the world” rather than more melee weapon variants. Telemetry revealed retention drops during the second boss fight. At the same time, interviews with heavy users suggested linking part of progression to environmental storytelling — advancement through discovery and understanding of the world rather than XP alone. Each lore element could grant something concrete: a perk, a function, an energy-cost modifier, a shortcut, or a contextual action.

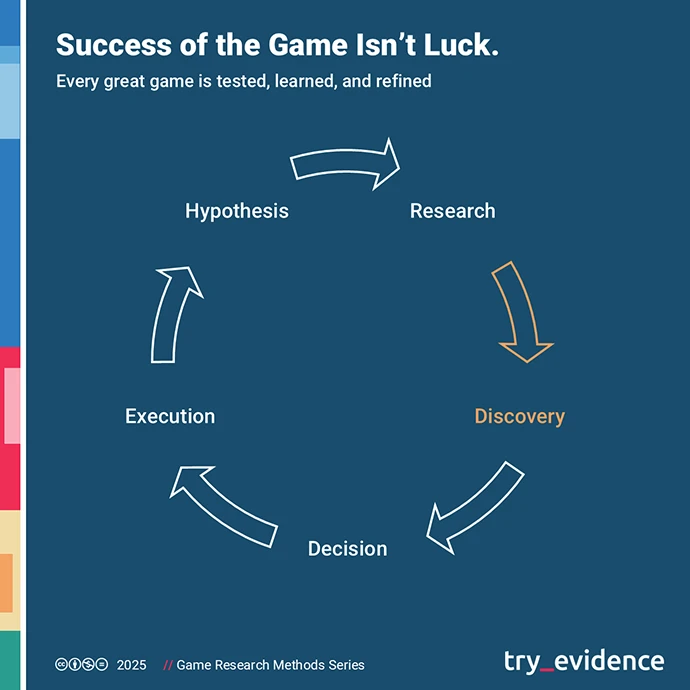

Post-launch research closes the same loop as before: intuition/hypothesis – research – discovery – decision.

Takeaway:

- We synthesize incoming signals. Post-launch ethnography (Steam reviews, Discord/Reddit, media, influencers) combined with IDIs across three cohorts (drop-offs, 2h+ players, heavy users) helps us map what happens — and why.

- We merge qualitative insights with telemetry. We align themes and emotions with data points (retention, drop-off moments, refunds, boss-fight telemetry, Steam algorithm signals) to locate intervention areas.

- We translate findings into the roadmap. Patch priorities (clarity, balance, UX) and DLC directions (player fantasies, progression through world-building) are estimated for their potential impact on retention and sales.

Success of the Game Isn’t Luck. It’s Research Done Right.

A game is never a matter of luck — it’s a consciously designed experience that makes sense both psychologically and commercially. Designing that experience means formulating hypotheses, crafting the right questions, collecting meaningful answers, making decisions, and applying adjustments.

Project Wraith illustrates a simple truth: everything works when, at every stage, we ask the right questions and choose the right research methods.

First: does the intended emotion and experience have an audience?

Then: does the core loop deliver it?

Next: does the full system still make sense once scaled?

Before launch: does the public promise match the real experience?

After launch: what can be fixed with a patch, and what deserves to evolve into DLC?

Research reduces the gap between intention and perception. It closes the perception gap and keeps the game’s concept aligned with both the market and what the player actually feels.

As Jesse Schell rightly suggests, a game designer is a researcher of emotions. We add methods and measurements to make those emotions and experiences intentional, testable, and measurable..

*

Disclaimer: any resemblance to real Try Evidence projects is purely coincidental. Project Wraith is a fictional case study created for illustrative purposes only.